by Jim Schlotter

In the summer of 1955, my older brother and I both came down with measles just around the first week or so of school. I was 5. Though we both began to recover, I felt sick again and lapsed into a coma overnight.

When I could not be awakened, I was rushed to the Children’s Hospital in Pittsburgh. They placed me in an isolated room in a ward with other children suffering the same infection. I woke up three days later to a great deal of howling from the patients in nearby rooms.

I didn’t know why I had been hospitalized, but it was greeted as something of a miracle that I knew and could spell my own name. My parents and siblings had been told to prepare for me to die. Three days later, I was sent home to recover, though I wouldn’t return to kindergarten until January.

I had survived encephalitis, or swelling of the brain. It’s an uncommon complication of measles, but because the disease itself was so common, a reported 1000 children suffered from this every year. Encephalitis frequently leads to death or permanent disability. I was lucky but not unaffected.

Measles’ Neurological Effects

My school prided itself on its academic prowess, and so we were tested early for IQ. What I noticed after being hospitalized is that despite scoring well in those tests, I found memorizing lists of names, events, or word spellings hard to organize in my brain. So my report cards were rich with comments about how I was not “living up to my potential.” This, of course, disturbed my parents, who made certain that it also disturbed me.

I had to develop ways to learn and keep up with classmates that leaned heavily on the association of one idea with another as opposed to memorizing facts. Even today, I can’t remember names, telephone numbers, addresses, and the like, but instead derive solutions to problems by identifying simpler, similar issues and then working up to the answer. My little coping mechanism worked well enough to keep in step with my more gifted peers. Once I was settled into the Advanced Placement curriculum, the general social assumption was that we were all more or less peculiar, but, at least, we had each other.

Long-term, I lost coordination, a significant part of my eyesight, and some of my organs were fever-damaged. I also began to experience an occasional feeling like a static spark at the back of my skull. In my early 60s, a neurologist at Capital Medical Center in WA helped me figure out why. I collapsed in the street and was given a CAT scan. It turns out the encephalitis left a pool of spinal fluid on top of my brain, which had dried and ossified through the years into something like a rock. When it presses on my brain, I receive a neural discharge which (very temporarily) blacks me out. For this reason, I stopped driving.

I Was One of the Lucky Ones

Of course, I have been extraordinarily lucky and have no complaints. My parents were convinced that I would not be able to beget children, would not be able to lead a normal life, and would die young. Many of those children who were much more severely damaged than I could have lived healthy lives if there had been a measles vaccine in 1955.

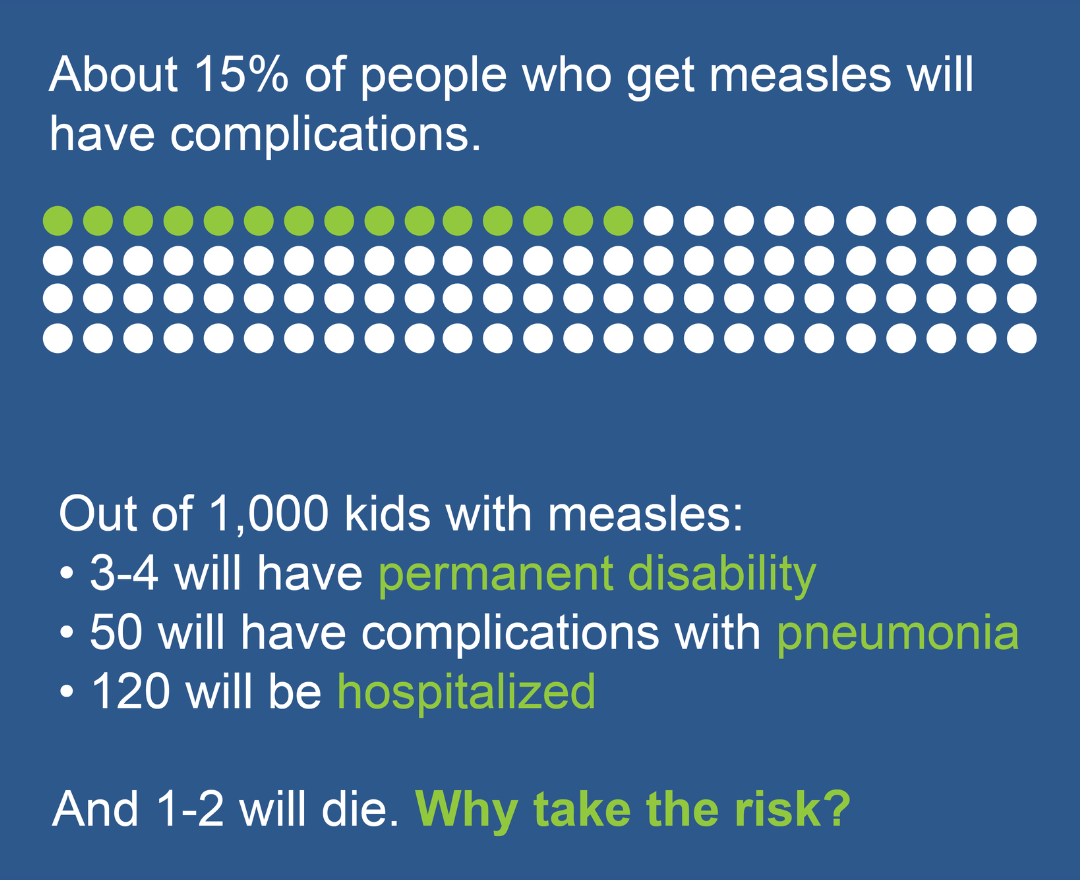

As chilling as the details of my medical past are, and I try not to think about them often, they inform my feelings about vaccines. It is a question of relative benefits versus relative costs. Certainly, no medical treatments result in 100% success without side effects. But statistically, there tend to be many more successes than is the case when the disease is left to take its natural course. The measles vaccine can prevent nearly all cases of the disease, and since its complications are often crippling if not deadly, we should not turn away from its benefits.

At 74, I have lived a very full and satisfying life. But I am only one person out of more victims than I know the count. No solution I reached for myself can give the dead back their lives or give the disabled a full and meaningful life. It depresses me, and the thought is always near.

Jim Schlotter is a retired strategic planner and project manager who lives with his wife in the state of Washington. His story, like all others on this blog, was a voluntary submission. If you want to help make a difference, submit your own post by emailing us through our contact form. We depend on real people like you sharing experience to protect others from misinformation.