by Anita Mantz

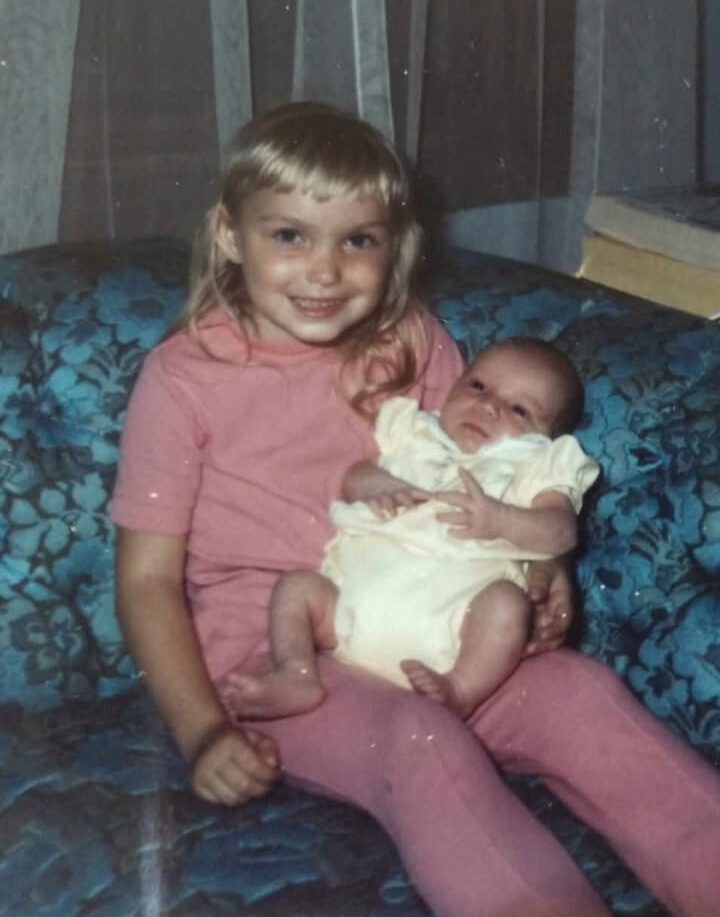

My sister Dreama, who was 13, could only say a few words. Since I grew up with it, I didn’t know how unusual this was. She could walk then, but soon someone always had to be able to carry Dreama, or “sissy” as we called her, through the house or to the car.

In 1972, six years before I was born, my sister got measles. My mom always told me that this is why she was sick, but I was probably 8 years old when she finally explained the whole thing to me.

Dreama was smart as a whip. Her principal would later say that she was astounded by her intelligence and that she was a popular, promising girl. But after she got measles, she began to fall behind in school and lose coordination. That was the end of a normal seven-year-old child.

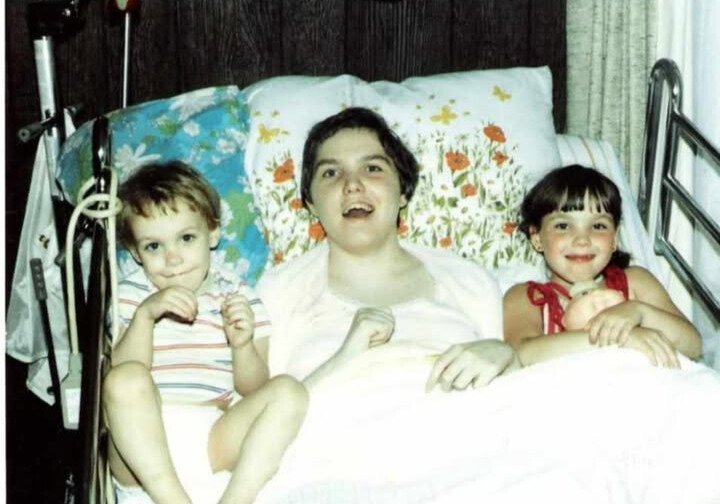

Over the next 14 years, she would slowly lose all functions. She was diagnosed with SSPE, known then as Dawson’s Encephalitis, a rare but almost always fatal complication of measles which affects your brain.

This meant my childhood was not normal, either. Growing up we had a hospital bed in our living room, with physical therapists, home health aides, and others coming and going.

My mom started taking her to see a doctor in Detroit, the only one she could find who was remotely familiar with SSPE. She was given a stapled packet listing everyone who had this disease at that time, which had about 200 names. Mom became friends with two of the other parents whose children had this disease. We visited them when we could.

Mom always said she would take care of Dreama as best she could, as long as she could. Some other parents sent their children away to facilities. She was supposed to tour a home called Apple Creek but heard about a case of patient neglect, and said she could never send her daughter to a place like that.

When mom finally explained Dreama’s illness to me, I asked her why she didn’t sue the school, since that had been where Dreama was exposed to measles. She asked, “Would that make her better?” Our concern was for her.

Dreama’s Last Years

Someone always had to be home with her. At the age of nine, I could set up her tube feeds and change her oxygen. I stayed up on weekends to help suction her throat when she coughed. My parents never asked me to do any of it, but I saw their struggles so I would help when I could.

We couldn’t have had a better family around us through it all. Originally from West Virginia, my mother had nine siblings who would visit us in Cleveland when they could. My uncle Gary planned to move his family to Florida, but told my mom he would delay the move as long as she continued to care for Dreama. So his family stayed there for four years after they’d made up their minds. In that way, Dreama’s life affected my aunt, uncle, and their children’s lives too.

Dreama passed away in 1988. Not a day goes by when I don’t think I don’t think of her. I often wonder what she would be doing if she’d never gotten sick, and believe she would be accomplishing great things today.

Seeing measles come back shook me hard. It has me anxious and furious and a complete mess. It’s completely senseless, and I wish people who say measles is nothing could have a look at my life.

I watched my sister die a slow death. If you could prevent the chance of this happening to your child, why would you even question that?

Dreama Sue Hager

1964-1988

Anita Mantz is a former factory worker who lives in Ohio with her husband, daughter, and dog. Her story, like all others on this blog, was a voluntary submission. If you want to help make a difference, submit your own post by emailing us through our contact form. We depend on real people like you sharing experience to protect others from misinformation.