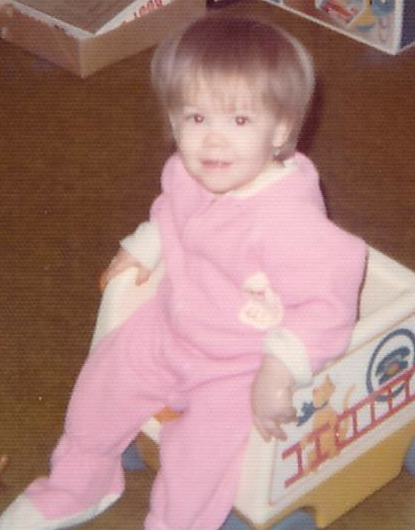

In many ways, 1974 was the good old days. Jim Croce was saving time in a bottle and Connect Four sat under almost every Christmas tree. The speed limit was reduced to 55 mph, which was a good thing for me, because my primary seat belt was Mom’s arm.

And parents weren’t subjected to Internet misinformation about immunization or false claims about vaccines and autism. They didn’t worry about how many vaccines their children received, only that they received them—and they were glad to protect their children against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, measles, mumps, rubella, and polio. After all, most parents of 1970s children were very familiar with those diseases: either they suffered from them as children or knew others who had. Our parents knew that not all children who got sick from these diseases survived them. Protecting their own children was a no-brainer.

As great as 1974 was, though, that year ended in illness for me. I was a year old and hospitalized with pneumonia as Christmas approached. My family members, also very ill, could not visit me, and I was left in my net-encased crib to recover. It’s important not to downplay the seriousness of hospitalizing a child. To this day, my mother talks about the powerlessness of having a very sick child left in the hands of others and all the fear and sadness that accompanied my serious case of pneumonia.

As great as 1974 was, though, that year ended in illness for me. I was a year old and hospitalized with pneumonia as Christmas approached. My family members, also very ill, could not visit me, and I was left in my net-encased crib to recover. It’s important not to downplay the seriousness of hospitalizing a child. To this day, my mother talks about the powerlessness of having a very sick child left in the hands of others and all the fear and sadness that accompanied my serious case of pneumonia.

You don’t have to tell me that pneumonia is a bad deal. While I recovered, today–forty years later–pneumonia is the number one killer of children under the age of five worldwide, causing the deaths of over a million children every year.

Children growing up today in the United States are lucky. The twenty-first century has brought us so many ways to protect them. We’ve replaced mom’s arm with modern car seats and seat belts. And we can immunize children to protect them against pneumococcal disease in its many forms, from sinus and ear infections to more serious complications like a severe upper respiratory infection (pneumonia), a life-threatening swelling of the brain (meningitis), and life-threatening and difficult to treat blood infections. Being hospitalized with pneumonia, meningitis, or blood infections means being tethered by IVs, possibly undergoing brain surgery, receiving antibiotics, and being at risk after treatment for complications like hearing loss or brain damage.

The vaccine that protects against pneumococcal disease has done remarkable work since being licensed in 2000. Not only has it nearly eliminate pneumococcal disease caused by the serotypes covered in the vaccine, but it has also reduced hospitalization rates of those not vaccinated by 50%. This vaccine not only protects our children–it also protects our communities.

While I am glad that it is no longer 1974 and that we can better protect our children, we still have twenty-first century problems. We have friends and neighbors who worry about how many vaccines their children receive and wonder if protecting them against the devastating diseases that struck fear in our parents’ and grandparents’ hearts is worth the number of injections our children receive. After all, children can receive twenty-six injections before entering kindergarten, and those injections sometimes result in tears.

Those who create our vaccine schedule (ACIP) keep in mind the various costs of our immunization schedule–from the real financial cost to the less tangible costs. They do listen to the concerns of parents. Weighing these costs means that members of ACIP are considering recommending one less dose of the pneumococcal vaccine in the U. S. vaccine schedule.

The science behind changing the doses is under debate. But it does seem that we might see more more illness with fewer doses of the pneumococcal vaccine. According to Dr. Paul Offit, we could expect 7.8 per 1,000 more hospital admissions with fewer pneumococcal doses. We could also expect children most at risk–those with chronic conditions or weaker immune systems–to suffer the brunt of a less robust immunization dosage recommendation.

What about the other costs? Would eliminating one dose ease a parent’s mind? Do most parents even need that reassurance?

My children have both received the recommended four doses of the PCV7 (pneumococcal conjugate 7-valent) vaccine–the vaccine that protects against seven serotypes of pneumococcal bacteria. I’m happy to report they have never had pneumonia or even an ear infection. In this way, they are like the vast majority of children their age in the United States, and I am like the vast majority of parents. Parents like us choose to protect our children from a disease we know can be cruel to children and communities, and one more dose for greater protection brings us peace.

My children have both received the recommended four doses of the PCV7 (pneumococcal conjugate 7-valent) vaccine–the vaccine that protects against seven serotypes of pneumococcal bacteria. I’m happy to report they have never had pneumonia or even an ear infection. In this way, they are like the vast majority of children their age in the United States, and I am like the vast majority of parents. Parents like us choose to protect our children from a disease we know can be cruel to children and communities, and one more dose for greater protection brings us peace.

In fact, my youngest son was three years old when PCV13 (pneumococcal conjugate 13-valent), which protects against thirteen serotypes, became available. He was beyond the normal age to receive this vaccine, and he was not at high risk for meningitis, pneumonia, or blood infections. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended that children his age receive an extra dose of pneumococcal vaccine to protect them and their communities against those additional six strains of the pneumococcal disease.

I did take him in for a special appointment just for that extra vaccine dose. The nurse at the appointment and the doctor who ordered the vaccine were in agreement that another injection–a fifth injection no less–was worth the added protection. But after the nurse gave my son his shot, he was mad. It hurt and he did not like it, but then we went out to his favorite local diner and chatted it up with his favorite waitress, and he was fine. And I was relieved that he had the extra protection and that he would not pass along this really terrible illness to a baby who might end up in the hospital like I had.

That’s the kind of time we should save in a bottle. The time that gives children long, happy childhoods.